Writing Point of View - Part 2

In my previous post, I covered the basics of point of view (POV) and included an explanation of omniscient POV. Today I will describe third-person-limited and first-person POV.

Third-person-limited POV is similar to omniscient in that the writer employs third-person pronouns (he, she, it, they, them) for all characters, including the POV (focal) character. It is called "limited," because the writer describes only what the scene’s focal character sees, hears, smells, touches, or knows about.

For example, the following is the beginning of a scene written using this type of POV with Adrian as the focal character.

Adrian dropped to his knees and laid Marcelle on the ground. As he panted, cold air swirled, and light drizzle added wetness to his sweat-drenched tunic. Wallace and Shellinda, their sleeves now covering their arms, plopped down beside him. Both tilted their heads upward and opened their mouths to catch the tiny drops and quench their thirsts.

“Take your time and get as much as you can,” Adrian said. “We’ll rest here awhile.”

Wallace laid the sword on the ground. “Want me to carry her? You need a break.”

Adrian rubbed an aching bicep. As he pressed a thumb deeply into the muscle, it loosened a bit, enough to ease the pain. “I’ll be all right. Thanks anyway.”

Notice that the scene begins with the character's name and describes something he does in order to signal readers that they will experience this scene through this character's senses. Beginning a scene this way is not an essential element of this kind of POV, but it is helpful to situate the reader.

Through Adrian's senses, readers feel the swirling cold air, the drizzle, and the sweat. Then, through Adrian's eyes, readers see two characters sit and drink from the falling rain.

Like the omniscient option, this POV can allow readers to become intimately acquainted with multiple characters, but only if the author switches POV among those characters. Some stories have a single POV character throughout, while others switch among characters from time to time.

If an author wants to tell a story from multiple viewpoints, it is better to wait for the end of a scene to switch the viewpoint from one character to another. If the viewpoint switches within a scene, readers might become confused about which character they are seeing the story through.

For example:

"Want some buttermilk?" July asked, going to the crock.

"No, sir," Joe said. He hated buttermilk, but July loved it so that he always asked anyway.

"You ask him that every night," Elmira said from the edge of the loft. It irritated her that July came home and did exactly the same things day after day.

"Stop asking him," she said sharply. "Let him get his own buttermilk if he wants any. It's been four months now and he ain't drunk a drop—looks like you'd let it go."

She spoke with a heat that surprised July. Elmira could get angry about almost anything, it seemed. Why would it matter if he invited the boy to have a drink of buttermilk? All he had to do was say no, which he had. (Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove)

The first perspective we notice is Joe's. We get an explanation of why he asked for buttermilk, which comes from his point of view. Then we get a dose of Elmira's perspective. We learn that she is irritated about July coming home. We couldn't know this unless the story is being told in her perspective. Then we get a glimpse from July's perspective. We wouldn't know that the heat surprised July unless the story is being told in July's perspective.

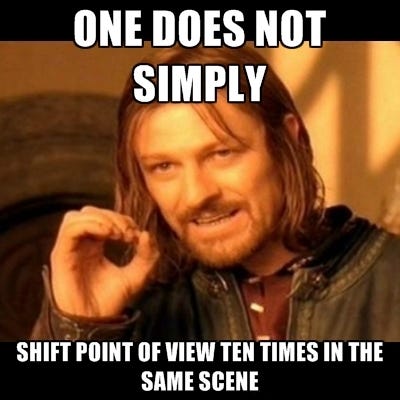

As you can see, some writers switch POV frequently. This is often called head-hopping, which can be jarring to readers.

If a mid-scene switch is absolutely necessary, then show the break with white space or a symbol to let the reader know that a shift is occurring.

As you are writing, if essential mid-scene switches become too common, then consider using omniscient POV instead of third person limited.

First-person POV is similar to third-person-limited in that the author describes only what the focal character sees, hears, smells, touches, or knows about. With first-person POV, the focal character is the storyteller, and the writer employs first-person pronouns (I, we, us, our) for that character and third-person pronouns for other characters.

For example:

The death alarm sounded, that phantom punch in the gut I always dreaded. I touched the metallic gateway valve embedded in my chest at the top of my sternum—warm but not yet hot. The alarm was real. Someone in my territory would die tonight, and I had to find the poor soul. Death didn’t care about the late hour. Reapers like me always stayed on call.

Every sensation comes through the "I" character--visuals, feelings, and even thoughts. Stories written in first-person POV usually do not shift to another character throughout the story. The "I" character is the main character and storyteller, so shifting to a different character skews the idea that this character is really the storyteller. I think an author needs to have an excellent reason to shift to a different character when using this POV, but such reasons do exist.

Beginning in the next post, I will go into detail about implementing POV in ways that will help readers attach to your characters intimately and become engrossed in your story.

For more writing help, consider my book, Write Them In - Click Here to Buy

Also available on Amazon - Click Here